Occasionally, I get questions about how to unpack PyInstaller executables using

pyinstxtractor, how to identify the script of interest among the bunch of extracted files etc. In this post, I intend to cover all of these. Let's get started.

The file for our purpose is a

recently identified ransomware having the following SHA256 hash.

Sample Hash: 53854221c6c1fa513d6ecf83385518dbd8b0afefd9661f6ad831a5acf33c0f8e

Download from Mega (Password: infected)

Preliminary Analysis

The executable "hc6.exe" has the following icon. The icon itself is a tell-tale sign that it's a PyInstaller executable.

|

| Figure 1: Icon |

Another way we can identify such files is by dropping it in a hex editor. A PyInstaller generated executable has many strings referencing python, towards the end of the binary.

|

| Figure 2: Strings |

A PyInstaller executable consists of two parts - a bootloader and a zlib archive appended to it as an overlay. The purpose of the loader is to set up the Python environment for running the application. This includes loading the Python DLL from the filesystem or from memory when the DLL is bundled within the executable. After going through a series of operations, finally it executes the main script and the control is transferred to user code. The loader also sets up hooks for resolving imports which are embedded within, the details of which are beyond the scope of this post. You can refer to the

source for more information.

Extracting

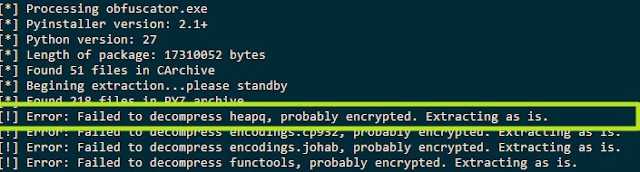

Knowing that the sample is a PyInstaller generated executable we can proceed to extract its contents using

pyinstxtractor as shown in Figure 3.

|

| Figure 3: Running pyinstxtractor |

The latest version (1.9) of

pyinstxtractor shows which scripts are the possible entry points to the application. These are the python scripts which are run when the application is launched. Naturally, we want to begin our analysis from here. In this sample, it has identified

pyiboot01_bootstrap and

hc6 as the entry points. Among the two, the former is

PyInstaller specific and not of interest. The other one named

hc6 does sound interesting. Let's have a look at the contents of the extracted directory before analyzing the file hc6.

|

| Figure 4: The extracted contents |

Within the extracted directory we can see a bunch of stuff - DLL files, Python C Extensions (PYD) and also a sub-directory

out00-PYZ.pyz_extracted. This nested sub-directory just contains compiled python files (PYC) as shown in Figure 5. The

pyc files are from the standard python library or from a 3rd party library such as PyCrypto. Hence, in this sample, we can exclude these files from analysis.

|

| Figure 5: pyc files inside the pyz |

Decompiling the main script

The main script or the entry script is named hc6, let's have a look in a hex editor.

|

| Figure 6: hc6 in a hex editor |

This does not look like python code, does it? However, this was not the case in earlier versions of PyInstaller, where the main script was left as-is, in plain text. Recent versions,

compile the py source to bytecode before packaging it in the executable.

We now want to decompile this bytecode file back to python source, however, in its present form a decompiler wouldn't recognize this as a valid

pyc file. The reason for this is that the magic value (i.e. the signature) is missing from this file header. A Python 2.7 pyc file begins with the bytes

03 F3 0D 0A followed by a four-byte timestamp indicating when this file was compiled. We can add these 8 bytes as shown in Figure 7.

|

| Figure 7: Adding the missing header |

With the above changes, we can now feed this file to a decompiler such as

pycdc. In case you do not want to compile yourself, I have provided precompiled binaries at

AppVeyor. Decompiling we get back the source.

Analyzing the ransomware

Finally, we can have a look at the ransomware in all its glory. It encrypts files from the following list of extensions.

.txt, .exe, .php, .pl, .7z, .rar, .m4a, .wma, .avi, .wmv, .csv, .d3dbsp, .sc2save, .sie, .sum, .ibank, .t13, .t12, .qdf, .gdb, .tax, .pkpass, .bc6, .bc7, .bkp, .qic, .bkf, .sidn, .sidd, .mddata, .itl, .itdb, .icxs, .hvpl, .hplg, .hkdb, .mdbackup, .syncdb, .gho, .cas, .svg, .map, .wmo, .itm, .sb, .fos, .mcgame, .vdf, .ztmp, .sis, .sid, .ncf, .menu, .layout, .dmp, .blob, .esm, .001, .vtf, .dazip, .fpk, .mlx, .kf, .iwd, .vpk, .tor, .psk, .rim, .w3x, .fsh, .ntl, .arch00, .lvl, .snx, .cfr, .ff, .vpp_pc, .lrf, .m2, .mcmeta, .vfs0, .mpqge, .kdb, .db0, .mp3, .upx, .rofl, .hkx, .bar, .upk, .das, .iwi, .litemod, .asset, .forge, .ltx, .bsa, .apk, .re4, .sav, .lbf, .slm, .bik, .epk, .rgss3a, .pak, .big, .unity3d, .wotreplay, .xxx, .desc, .py, .m3u, .flv, .js, .css, .rb, .png, .jpeg, .p7c, .p7b, .p12, .pfx, .pem, .crt, .cer, .der, .x3f, .srw, .pef, .ptx, .r3d, .rw2, .rwl, .raw, .raf, .orf, .nrw, .mrwref, .mef, .erf, .kdc, .dcr, .cr2, .crw, .bay, .sr2, .srf, .arw, .3fr, .dng, .jpeg, .jpg, .cdr, .indd, .ai, .eps, .pdf, .pdd, .psd, .dbfv, .mdf, .wb2, .rtf, .wpd, .dxg, .xf, .dwg, .pst, .accdb, .mdb, .pptm, .pptx, .ppt, .xlk, .xlsb, .xlsm, .xlsx, .xls, .wps, .docm, .docx, .doc, .odb, .odc, .odm, .odp, .ods, .odt, .sql, .zip, .tar, .tar.gz, .tgz, .biz, .ocx, .html, .htm, .3gp, .srt, .cpp, .mid, .mkv, .mov, .asf, .mpeg, .vob, .mpg, .fla, .swf, .wav, .qcow2, .vdi, .vmdk, .vmx, .gpg, .aes, .ARC, .PAQ, .tar.bz2, .tbk, .bak, .djv, .djvu, .bmp, .cgm, .tif, .tiff, .NEF, .cmd, .class, .jar, .java, .asp, .brd, .sch, .dch, .dip, .vbs, .asm, .pas, .ldf, .ibd, .MYI, .MYD, .frm, .dbf, .SQLITEDB, .SQLITE3, .asc, .lay6, .lay, .ms11 (Security copy), .sldm, .sldx, .ppsm, .ppsx, .ppam, .docb, .mml, .sxm, .otg, .slk, .xlw, .xlt, .xlm, .xlc, .dif, .stc, .sxc, .ots, .ods, .hwp, .dotm, .dotx, .docm, .DOT, .max, .xml, .uot, .stw, .sxw, .ott, .csr, .key, wallet.dat

Encrypted files have an extension of .fucku appended to the original filename. This can be seen in the decompiled code as shown below.

|

| Figure 8: Supported extensions |

Files are encrypted with the AES cipher in CBC mode with a random IV generated per file.

|

| Figure 9: Files are encrypted using AES |

AES is no doubt a strong algorithm and infeasible to crack. However, the ransomware encrypts each file using a constant and hardcoded key which makes decryption feasible. This is shown in the figure below. The AES key used is j<L;G|hD*3CQk%I!g|Ei&#aQ6*;Vh,

|

| Figure 10: Look, the password is hardcoded! |

Decrypting encrypted files

Since we know that each files are encrypted with the same key we can develop a decrypter. However, our kind ransomware author has spared us the bother by providing the decrypter in the same code.

|

| Figure 11: Bundled decrypter |

The function

decrypt decrypts an encrypted file. It's not called from anywhere, indicating it was there for testing purposes and was not removed in the final build.

There is no need to pay the ransom if someone is infected by this ransomware. A

free decrypter is available from the malware hunter team. Kudos to them for their fabulous work!